Is Social Justice Biblical?

Biblical justice vs. social justice: Is social justice in the Bible? What is biblical justice, and what is the relation between Christians and social justice?

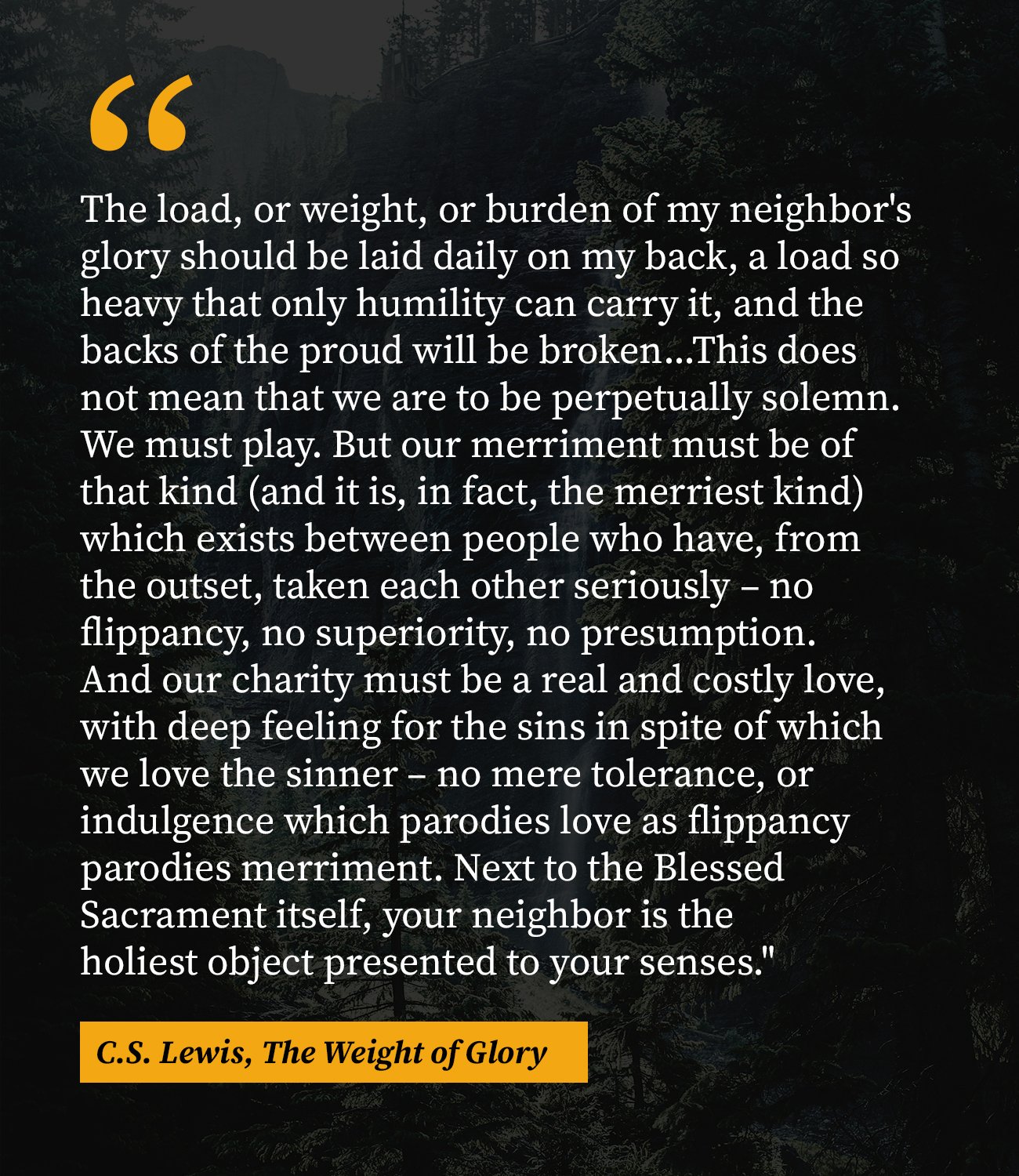

Excerpt from C.S. Lewis’ The Weight of Glory

The weight of social injustices and the issue of justice have been heavy on us the past decade, and at times, it's been crushing. The work of restoration is solemn and hard but one day will be rewarded in heaven.

Until then, these questions of justice, social justice, and the church come with a lot of pressure and baggage. However, I think the answer is what C.S. Lewis says—the only way to carry that weight is with humility.

Our cultural moment is like a cartoon, where two people stand on the opposite sides of a number six. One person is looking down, and saying, "That is a number six!" Then the other person is standing on the opposite side of the number, and they're saying, "No! That is a number nine!" So, they're looking at the same thing, but they're coming in from a different perspective. But they are seemingly living in an unbridgeable divide.

That is where we’ve been with the rise in social justice. There are people on the opposite sides of multiple divides saying, “Don’t you see?”

We are trying to name God's vision of justice, but we have been looking at the Bible from different perspectives. What we need is the humility to step on the other side to see our neighbor's viewpoint and invite them to do the same with ours.

So let's start with some common ground to stand on and a perspective on biblical justice.

What is Biblical Justice?

Biblical justice is throughout Scripture. God is just, and justice overflows out of His character, His Love, and His Holiness. But the world is broken and full of sin and gross injustice. So when we talk about biblical justice, it is the idea of God's redemption that brings back peace, fairness, equity, and shalom—which is the right relationship with God and others in the world around us.

We're not creating something new when we aim for justice; we're going back to how God intended things to be. Ultimately, biblical justice is God's rescue mission.

How Do We Find Shalom?

Paradise has been lost, but it’s being regained through Christ and His kingdom. This mission is found throughout Scripture from start to finish, and it is one that Christians should be passionate about.

We want this idea of shalom, but it gets messy in execution. As Christians, we're called, right now, to live on this earth as if the new creation is breaking in. According to the ethics of new creation, the church is supposed to be the one outpost in enemy territory where we live as Kingdom citizens under Jesus. Those ethics are the Sermon on the Mount.

The righteous indignation that bubbles and is on a bursting point in our hearts at all the injustice in the world is a good thing. It reveals how you were designed. We were designed for Eden, a place of perfectly flourishing relationships between God and man and between each other.

However, the fire needs to be controlled, or it will blaze over everything rather than refining the good and burning away the bad. The church is the one place, the fireplace, where all that fuel and kindling is meant to go. Lit with the light of Christ and the burning desire of our hearts, the church becomes that city on a hill with its lights shining for all to see.

In his article "Justice in the Bible,” Tim Killer lays out five themes of what Biblical Justice is.

Five Themes of Biblical Justice

1) Community

The one thing about the church is that it is the place where you can bring the gifts God has given you—those talents He has asked you to steward—and, out a response to Jesus' love for you, offer them back to God and give them to your neighbor.

However, because God is Love, everything is a choice. The choice to give is not mandated or compelled but free, and this generosity comes, totally, from the heart. This kind of Biblical community cuts through our worldly ideologies.

The result of that self-giving love that creates community is Trinitarian. The Father and the Son love each other and give themselves to each other in such a tremendous capacity that their love becomes a person, the Spirit.

Moreover, as Proverbs 11 says, when the righteous prosper, the city flourishes. Biblical community is not a call to laziness or lack of work. It's saying that when the righteous prosper and do work in this way, the result will not just be that they are blessed, but that the entire city will be blessed and flourish and will rejoice in the Lord. (Remember, Justice is God's rescue mission!)

The church has to be the one place, the outpost of the kingdom of God in enemy territory, where everyone comes in on equal footing. The world stands on the stratification of worth. But the church is where the CEO can sit next to the single mother and be completely equal, on the same footing, at the foot of the cross and the throne of God.

2) Equality

(note: Keller uses Equity, but that word is itself ambiguous given that many post-modern theorists use the word in highly specific, idiosyncratic ways. For our purposes, we’ll use the more neutral word Equality)

Biblical justice means everyone must be treated equally and with dignity. This is because we're all created in the image of God, the Imago Dei, and that is the basis by which we have rights and by which we have our identity.

I love what C.S. Lewis says elsewhere in The Weight of Glory, that you have never met a mere mortal. There's no such thing as an ordinary person. Everyone is either destined for eternal glory or eternal horror. If we can see everyone with those eyes as being children of God, with a potential destiny of life with Him in glory or life apart from Him is agony, that will change the way we act towards our neighbor.

The Imago Dei completely differentiates a secular view of justice and a biblical view of justice. While there's overlap, we have this equality through our creation and our Creator completely changes everything.

We take our assumptions about justice and rights as a given sensibility—common sense universal to all humankind for all time. But that was utterly foreign to humanity before Christ. The norm of human nature was domination. It was a kind of Thomas Hobbes' State of Nature ethic. The ethic wasn't the Sermon on the Mount; it was Social Darwinism—survival of the fittest. Aristotle said, in Nicomachean Ethics, that some people are created to be tools, and some people were made to be slaves, and their purpose in life is to be a slave. Aristotle said that! Yet, that ethic was acceptable and lauded in the ancient world.

Our ideas of inalienable rights were alien to them. But then here comes Christ, with a radical ethic of pouring oneself out for the sake of others. Here come the ancient Hebrews saying God made us all in His image. This idea of the individual’s inherent worth and of loving one's neighbor was radical. When one takes this transcendent grounding of our human rights out of the picture, our human rights have no basis.

So if you are that person who has righteous indignation against infringement of human rights, that indignation is thoroughly Christian. Therefore, I pray that what God began in you, He brings to completion and that you can find a home for that burning desire in the furnace of the church.

However, when many Christians look at the church, they see hypocrisy. In a recent Christianity Today article, Russell Moore made the point that millennials and Gen Z'ers are not leaving the church because of what the church teaches or believes. Instead, they're leaving the church because the church is not following this ethic of equality. Tim Keller also adds this:

"One of the many reasons for the decline of church-going and religion in the U.S. is that increasingly Christians are seen as highly partisan foot-soldiers for political movements…When the church as a whole is no longer seen as speaking to questions that transcend politics, and when it is no longer united by a common faith that transcends politics, then the world sees strong evidence that Nietzsche, Freud, and Marx were right, that religion is just a cover for people wanting to get their way in the world."

I think what Keller said is the same thing that Moore is saying. People look at the church, and they see a red and blue co-opting of faith for the means of a political agenda. That is heartbreaking, but Christ's Church is the place where new creation breaks. Justice is God's rescue mission, and the church is the headquarters. We cannot be content to just go to church and be church-goers. We need to be the church and be kingdom citizens.

3) Corporate Responsibility

Corporate responsibility is the idea that I am sometimes responsible for and involved in other people's sins. And that is a hot-button topic in today's world, especially in Protestant Evangelicalism.

In Divided by Faith, Christian Smith and Michael Emerson say that the evangelical psychological toolbox struggles with seeing structure. The way that we view sin and salvation and work ethic prevents us from conceptualizing the idea of structural sin, corporate sin, and corporate responsibility. It is all foreign to us. It's like we're trying to fix something. But we don't have the tool to do it in our minds. So, therefore, we approach it with all this suspicion, hesitation, and frustration.

But it's a crucial thing to understand. We must see the corporate and familial nature of both the Old Testament and New Testament. We must see the effect our sin has on others and on the environments, cities, and world we live in.

We have the built-in assumption in our Western culture that everything is very individual, even down to our theology. Everything hinges on a balance of individual guilt and innocence. But in an Eastern reading of Scripture, the whole crisis with God is corporate shame and honor. So, it is a lot harder for people who have grown up in Western evangelical cultures to even admit any level of corporate responsibility regarding justice issues.

In Daniel 9, Daniel repents for sins committed by his ancestors, even though there is no evidence that he participated in them. A personal mantra of mine is to “over repent.” We, as humans, have a bad sense of what our sins are. Many of them, as David says, are hidden faults. The same is true for corporate sin. When in doubt, accept responsibility and choose the path of humility.

In our cultural moment, the great divide is over racism and the historical consequences of slavery. I am not equipped or able to untangle that gordian knot, but what I can do, as a Christian who is white, is repent for the corporate sin of slavery, even if I was not the individual perpetrator, and humbly try to love my African-American neighbors as I would myself.

As British theologian Lesslie Newbigin said, "None of us can be made whole till we are made whole together." North American priest and author Tish Harrison Warren adds, "If we are saved at all, we are saved together." Shame and guilt aren’t the motivation here. It is love that is actualized through humility.

4) Individual Responsibility

Christianity sees sin as both personal and internal and communal and structural. It holds both of those together at the same time without compromising either. The delicate balance between corporate and individual responsibility is another great example of how a Christian ethic transcends the political spectrum.

The individual and the corporate work together in the kingdom and salvation; if it comes to the one, it must come to the many. We must be Christians of the cross—admitting our personal sins and finding a personal savior—and Christians of the kingdom—working for shalom and new creation in our neighborhoods, cities, and world. Together, we'll be Christians of the crown—enjoying the life and glory of God together.

Part of Shalom's more comprehensive restoration project entails not pointing out the speck of dust in our brother's eyes but turning in and taking out the log in our own eyes first.

“If you’ve tasted grace, you will be a just person. You will know the debt paid for you. How could you not show grace to others?”

As Lewis says, the only thing that can carry the weight of a neighbor's glory is humility. And that's what Paul is talking about when he says, Let your gentleness be evident to all. You can only come to that point of humility and gentleness by recognizing how broken you were and how much grace you've been given.

The church has always maintained that there are sins of commission (actively doing something wrong) and sins of omission (failing to do what is right). Yet, we tend to only account for sins of commission. We have a proclivity to see sin only as outward action, and we typically only see injustice as things that I'm outwardly doing. We fail to see that injustice is not just doing the wrong things but failing to do the right things. So my injustice is not just doing this act of injustice; it's my silence or indifference in the face of injustice.

Emerson and Smith say in Divided by Faith that we are like our own internal lawyers, always looking back at the past and saying, well, at least it's not as bad as this. In Jim Crow America, they were looking back and saying, well, we've gone so much further than slavery, we're good. Now we're able to look back and say, well, we're so much better than legal segregation. But, unfortunately, we're missing that there's the same thread of racial injustice extending on in the present in our city and nation.

A century ago, The London Times posed a question to the public, and anyone could submit a response. The question was, "What is wrong with the world?" You can only imagine the plethora of responses from people pointing to their various qualms with the world, politics, people groups, etc.

But GK Chesterton wrote back, "Dear Sirs, I am. Yours, GKC".

Rather than looking outwards with a spirit of revolution and protest, the first place to look is inward. The greatest revolution that needs to happen is the revolution of your heart turning over to Jesus. You can move outward from that place of inward grace with an orienting vision of what true grace and justice look like.

5) Advocacy

The last point of biblical justice is advocacy—having a special concern for the poor and the marginalized.

That's what led the church to explode. Emperor Julian the Apostate said in the fourth century that "It is a scandal that there is not a single Jew who is a beggar and that the godless Galileans [meaning Christians] care not only for their own poor but for ours as well; while those who belong to us look in vain for the help that we should render them."

He couldn't wrap his mind around what the Christians were doing in the fourth-century Roman world. The church exponentially grew due to this advocacy and whole life, biblical ethic of justice—that cared for the poor, invented hospitals, took in discarded babies from the street, and cared for widows. It was revolutionary, and I think we've lost it so much in our world because of polarization.

Keller explains that the early church had five tenants that they were committed to when it comes to advocacy.

They were committed to a conservative moral ethic regarding marriage and sex.

They were committed to caring for life, especially working against abortion, and caring for orphans and children that were discarded.

They were radically generous towards the poor.

They were multi-ethnic and multiracial.

They were non-retaliatory against their enemies.

In our western church today, Keller explains that churches or Christians can say, I can do the first two, but not those middle two. I can stand up for conservative sexual ethics. I can stand up against abortion and foster care, and adoption. But that's where I'll stop. Then you've got the other side saying, I can stand up for generosity and advocacy towards the poor. And I can stand up for a multiracial and multi-ethnic living, but that's where I'll stop.

Keller makes the point that no one's doing the non-retaliatory part! Those first four are fighting against each other.

How different would it be if the church could reclaim the Biblical advocacy that changed the world? In one breath, we could say that a flourishing marriage and sexual ethic look like this. Then the next, say, a flourishing city looks like this, and then turn around and say, it looks like this to care for babies in the womb, and then turn around and say, this is what it looks like to love across racial difference.

No one's doing that right now; no one's advocating for both of those things, right now, at the same time. But Christians can speak into that and uniquely enter into this conversation with Hope and Grace and hopefully get that fifth one down! This kind of advocacy would change the world. We know that because it did change the world in the first century.

Steps to Action & Change

Tish Harrison Warren in The Liturgy of the Ordinary says that often our theology is too big to touch our daily lives. So, by way of a conclusion, here are some suggestions of how can this big theology of biblical social justice can touch our everyday lives.

1) Start Where You Are

Historian Jemar Tisby has this great threefold analogy, an ark of racial justice. But we can extend this to all justice issues.

Awareness (walking)

Relationships (jogging)

Commitment (running)

Some of us with this conversation are at the walk/awareness level. If that is you, start reading and start listening. Explore this topic in Scripture, see where God is speaking about justice. Listen to diverse voices, racially, socio-economically, globally. Let God spark something in you.

After that, lean into relationships, that's the jogging moment. Pursue diverse friendships, have diverse relationships, serve or volunteer, seek out justice relationally in your life, and see that change your heart. The revolution of your own heart.

Finally, let that lead you to this commitment of running, of actually seeking systemic change in the city. This may be vocationally or volunteering with a nonprofit or maybe something within your church or your family or where you live or send your kids to school. What can I do differently to make my city more than just a city, but a just city?

Don't feel guilty about where you are. The important thing is to start somewhere. Love actualized through humility is the end and beginning.

2) Do the Dishes

Tish Harrison Warren shared a quotation that, "Everyone wants a revolution, but no one wants to do the dishes."

Many of us have a burning desire for revolution, but we have no outlet or agency. We want to critique the world, but all the while, our small worlds may be chaotic. So start small in your home, make it a place of shalom, wash the dishes, make your bed, make it an outpost of the kingdom of heaven in a war-torn world. Make it a place of community, of hospitality, of all the things that we talked about. Do the little things right. Then we will build the character, identity, and ability to handle those revolutions when God calls us to them.

3) Remember the Cross

Lastly, the reason why we can be just, the reason why we can pursue justice, and why we can make a change is because Christ took on what we deserved. On the cross, He bore the weight of what we deserved and died for us, but now He lives. He lives in us and is giving us His grace, and He is inviting us into God's rescue mission.

TL;DR

Biblical and social justice are much the same, only approached from different perspectives.

Biblical justice is a return to the way things were intended to be by God.

There are five themes to biblical justice: community, equity, corporate responsibility, individual responsibility, and advocacy.

Steps to action and change, include: start where you are, do the dishes, and remember the Cross.

Related Articles

A Seat At The Table For Everyone by Grant Caldwell

Loving Well Those We Disagree With by Rev. Jacky Gatliff

How Can I Help Others? by Bro. Chris Carter

About Christ Church Memphis

Christ Church Memphis is church in East Memphis, Tennessee. For more than 65 years, Christ Church has served the Memphis community. Every weekend, there are multiple worship opportunities including traditional, contemporary and blended services.